Interview with Joe McDonald - Professional Wildlife Photographer & Award-Winning Author

1. Hi Joe. How did you get started in wildlife photography?

I’ve been photographing wildlife since I was 13 years old, starting with the reptiles and amphibians I found around our home. Very early on, I made the mistake of trying to photograph a woodchuck, a hare-sized rodent, feeding in our backyard.

With my 35mm range-finder, the image I captured was a mere speck and I was disappointed. I started doing some research, discovered SLR cameras, and with the help of my very indulgent parents, switched to an SLR within the year.

My dad almost killed me when I casually told him that it wasn’t the camera that made good pictures, it was the telephoto lens I still had my eye on! He almost tossed me out of the car! Since then, I’ve never stopped shooting pictures, setting my sights ever higher for more exotic species.

2. Most nature photographers are married yet we never hear about their spouses. You work with Mary Ann on all your photo safaris, photo tours and digital photography courses - how did the two of you get this right!

A very hard-working woman is responsible!

We met when I did a talk at a local bird club, she took a workshop in the Florida Everglades I was doing, and the rest is history.

Early on, though, we had a pivotal talk on what our strengths were, what niche we could fill in the nature photography world, and what we wanted to do.

Most importantly, we agreed that personal egos were not important, that paying the bills and achieving our joint goals was the prize. That translates, then, into neither of us worrying about who got the better shot – if Mary gets it, great, and if I do, that’s fine, too.

Don’t misunderstand me, we are really competitive with one another but in the truest sense of fair play, so neither one of us slacks off thinking the other one will get the shot and the other doesn’t have to bother.

Our wildlife photography certainly has centered around our photo safaris and tours, and fortunately, although our personalities are different, we both enjoy working with and helping photographers and, more importantly, doing things together.

Frankly, I can’t imagine how couples who don’t work together manage to stay married, since so many wonderful experiences are not shared, and the time apart can be long. I guess that's why the divorce rate is so high.

3. You travel the world doing photo safaris - do you have a favorite location?

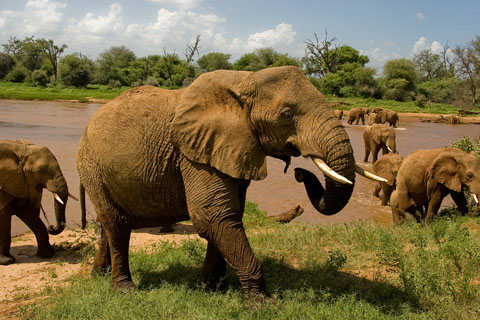

Africa is definitely our favorite continent, and our favorite location is Kenya’s Masai Mara.

There is so much to shoot and there is always the chance that absolute, true magic may unfold on any given day, so even when we’re tired, or the weather isn’t right, there’s still the possibility that this game drive, today, is going to be the most exciting shoot we’ve ever had.

I look with a lot of admiration at the work of the southern African photographers in Botswana and South Africa, and had we more experience in Botswana I might have a close second-choice.

For now, though, I’d have to say my next favorite destination is Brazil’s Pantanal, where we photograph a bit more limited selection of wildlife, but where jaguars provides the lure of those magical moments we’d love to capture.

4. Please give us an idea of a typical day on one of your African safaris...

Our day is pretty straight forward and typical of any safari, I’d think. We leave camp as soon as it is legal to drive, typically before sunrise, and return by noon, leaving again between 3 and 4, depending upon the light levels and heat, and returning at dusk.

Everyone is prepped, however, that if we have a hunt, or one looks imminent, we’ll stay out as long as is necessary, missing lunch if need be. Generally, no one has a problem with that as they are keen to see the behavior.

While both Mary and I love to capture action, we fully realize that for many of our participants a safari may be their first, and only, trip to Africa, the Pantanal, or wherever, and that it is important for everyone to photograph everything, and not just concentrate on the big cats.

As photographers, we think that actually works well for us, too. I’d suspect that photographers continually in the field might pass up the usual portrait of an impala or roller, but we can’t, so we’re probably stopping for subjects that we might pass on if we were on a personal mission.

We may not shoot, but we’ll have our gear out and ready, and if anything extraordinary happens we’ll be more likely to catch it. Consequently, I think our portfolios are rather diverse.

5. What are the most important criteria for someone wanting to choose a photographic safari? I ask this question as there are so many people offering safaris and I have heard some horror stories from photographers being crammed like sardines into safari vehicles to being stuck on safari with people they did not get on with.

They should do their homework, and not just look at the price, or the itinerary of a trip, but instead should look at the content. Unfortunately, far too frequently safaris are offered by photographers, perhaps even talented photographers, who have no experience in Africa or have little or very poor interpersonal skills.

Even worse, for some, leading a photo safari to Africa may simply be the easiest, or most profitable, means to get there, and the photo tour leader may have little sincere interest in the success or the happiness of his or her clients. Those horror stories, for us, are the worse, as it gives the whole business a bad name, and it certainly doesn’t have to be that way.

Experience is really important. Participants, especially first-timers, will probably be happy with anything and everything they get, but with an inexperienced guide they have the potential of missing a lot.

A photo guide with experience should be able to read behavior, and give a pretty good assessment of whether or not it might be worth waiting around for something to happen or to move on. Conversely, an experienced guide may recognize an alert posture, or hear a distant alarm call or whistle, or notice an unusual cluster of birds, which might indicate a predator is about.

From the anecdotes I’ve heard, disappointed clients often picked trips that visited multiple destinations instead of concentrating on a few very productive spots. While it might be tempting to believe one should see everything, in truth, one ends up spending more time travelling than photographing with those itineraries.

Regarding the last issue you raised, dealing with the interpersonal aspects of a safari, that’s a tough one which, I think, separates the successful leaders from the rest. We have a system that works, starting with having only three photographers per vehicle, so that everyone has their own windows and roof hatches.

But we go beyond that, and our system cultivates what many have described as a family atmosphere. That, I think, implies or requires a strong parental figure, with leaders that are capable and ready to take charge, to make decisions, and to stick with them. To give just one example, in our first briefing we expound upon the importance of promptness and the reasons why, and I make it clear that if people are late that those who are on time have our permission to start the game drive without the tardy ones.

Too often, one or two selfish individuals can, if permitted, infect a safari as everyone who follows the plans are forced to wait for the one or two who follow their own schedules. This breeds resentment, and can taint or poison a trip. A good safari requires a good team effort, with a team composed of clients, driver guides, and, most importantly, a competent team captain who coordinates and cultivates a winning atmosphere.

6. We have also seen some people advertising photographic courses where they promise "All you need is one lesson and in just 20 minutes you can be taking astonishing photos like a pro". Joe, you have spent the past 40 years as a wildlife photographer - are there any short cuts in progressing from taking snapshots to making good photographs?

I’m 58, and I’ve been photographing since I was 13, learning 80% of what I know from the famous school of Hard Knocks, from experience. That said, digital photography has certainly enabled a lot of photographers who have truly great eyes but little experience, or time or inclination to really learn.

If there are any shortcuts, or advice on same, I’d say ‘Shoot digital, as the learning curve is very steep, and mistakes can be seen and rectified within seconds, and not weeks as was required when we all shot film.

Unfortunately, not every shooting situation lends itself to mindless automatic metering or a complete disregard for contrast. Someone with a natural eye may not need lessons in composition, but an awareness of light and of contrast may still need to be instilled.

Frankly, we wish that everyone who did one of our safaris would have first invested some time in taking one of our photo courses, and if there was one other short cut, other than shooting digital, I’d say it would be to invest some time with a good instructor to learn the essential tenets of good photography and, today, in the importance of a good digital workflow, too. I could write a book filled with examples to support that advice, believe me!

7. You have published seven books of which we have three: The Complete Guide to Wildlife Photography; Designing Wildlife Photographs; Photographing on Safari. Are these books still in print and are they still relevant with digital cameras?

First, thanks for buying my books! Unfortunately none of these books are still in print, although old copies are sometimes offered on Amazon for 10X the original price! The Photographing on Safari book is still quite relevant, and recently I autographed a copy by a photographer who has carried his on every safari he’s made, always using it as a reference. I was honored.

Designing Wildlife dealt with seeing images and recognizing opportunities and composing, so its timeless I should think, as those concerns still apply today. Mary, a Photoshop guru friend, Rick Holt, and I did a digital version of ‘The Complete Guide …’ that addresses the world of digital, titled “Digital Nature Photography, From Capture to Output.”

I’m trying to find the time to do a new Safari Guide, either offered as a digital book or through a publisher, but with our travel schedule, and constant shooting, I’m not progressing very quickly. Hopefully, though, I’ll have that book written within the year.

8. Since you started photographing wildlife in 1966, what has been the most dramatic change for you besides the transition from film to digital?

The biggest change has been the sheer number of shooters out there, and the quality of the glass they’re using. Recently, a friend told me about a visit he made to a bald eagle site where perhaps a hundred photographers were lined up along the road, with a million dollars’ worth of glass. For the first twenty years I photographed, if you had a 400mm telephoto, you were probably a pro. Not anymore.

Fortunately, we rarely encounter other serious photographers when we are photographing on safari, except for our tour participants. Consequently, one can still capture rather unique images, and not just one variant on an endless number of essentially identical pictures.

The other absolutely radical change is in the professional marketplace. Again, when I started, stock photo agencies were accepting images that by today’s standards no photographer would consider submitting. The bar has certainly been raised, in terms of quality and because of the volume of photographers who would love to have something published, prices have dropped.

It would be very, very hard for a budding photographer to succeed today, although it certainly can be done if that person has the talent, drive, and, most likely, initial capital to start.

9. Are you and Mary Ann making use of the new camera features such as high ISO or video?

We love the high ISOs now available, and to us that’s one of the best features of digital photography. On our last Kenya trip we have many situations where we were using ISO 2000, an unthinkable option back in the days of film when an ISO of 400 was pushing quality.

I am not a fan of the video, and although I’ve used it – mostly as a toy, I cannot see where the average still shooter will actually use video. Sure, video can be incorporated into a PowerPoint program to jazz up a presentation, but if the audience is comprised of photographers they might question why it is even in there.

Further, shooting video demands video editing later on, so there’s another program to learn, or more time spent behind the computer doing it rather than being out there photographing.

10. You seem to have an affinity for flash photography, which can be difficult to master. Do you have any tips for photographers wanting to use fill-flash by day or for those wanting to take nocturnal photos?

I’d suspect that if there’s one aspect of photography I’m known for, it is flash.

I love using flash, but I stress flash should only be used when it is required. Often, on safari, I’ll watch with dismay as shooters, in low light, start shooting flash instead of raising the ISO and preserving the true ambience of the scene.

Flash can flatten a scene, and if there is intervening grass or brush between the subject and shooter there’s a good chance that the scene will suffer, as the lighting goes from bright to dark.

While it should be obvious, use flash only when it is needed, and for those on safari the two situations where that is most likely to occur is when there is no ambient light to make an exposure - at dusk or at night...

... or when the light is high, and contrast is high, with sharp shadows blocking up the subject.

With fill-flash in the latter situation, use less light rather than more, and, if your camera permits it, control the flash fill ratio from the camera, and not off the flash itself. In that way, should you wish to bracket the fill light you’ll find it easier to do.

11. What has been your most hilarious incident as a wildlife photographer?

On a mountain gorilla trek a big silverback decided to show its dominance over our Rwanda guide, and rushed over, grabbing his arm and pulling him down. Doing so, the gorilla’s arm stretched over one of our clients, who hunkered down, trying to look small and submissive.

To reinforce that, the woman started plucking and chewing on vegetation nearby. We were all kind of bent down, acting submissive, but as Mary and I glanced over and saw our wide-eyed friend picking and munching upon leaves, with her head almost in the gorilla’s armpit, we almost burst out laughing.

Discretion won out and we stayed quiet, and after a few seconds the gorilla released the guide and scuttled off through the vegetation, and our friend then stopped eating!

When we asked her why she started eating leaves, she told us she’d seen Diane Fossey do so in a film and it seemed like the best thing to do under the circumstances.

12. Tell us a bit more about your gorilla treks please Joe, they sound very interesting!

Mary and I have now led 55 mountain gorilla treks where we’ve brought along 5-6 other photographers with us.

That’s a park record – I can honestly say that no other photographer has the coverage we have, unless they’re associated with the parks in some way.

The next highest number is a guy with 35 treks, I’ve been told, but he comes solo.

We’ve found the park staff has been extremely appreciative of our visits, and we’ve shared that fact with the photographers who have accompanied us.

Photographing gorillas is tough, as the weather can be too sunny or raining too hard, or the gorillas can be nestled in deep, dark bamboo forests.

That’s why we’ve always done 5 treks for each tour, in order to maximize the chances that at least one day will be incredible.

On our last tour our luck was incredible, and all five days were magic!

13. Have you had any dangerous encounters with animals?

I’m happy to say almost never. Once, in Yellowstone, a bull elk charged across a meadow unexpectedly, as it chased a cow, and after it gave the bull the slip the elk put a bead on me. For a minute or so it was a bit tense as I worried that the elk would chase me around a tree.

Honestly, though, except for freak incidents like that where a photographer gets into a tight situation by just dumb bad luck, like rounding a trail and facing a mother bear, dangerous encounters shouldn’t occur.

I suspect there’s a hint of machismo with those who have stories, and I question if they might be pushing the envelope, interacting or stressing an animal and triggering an aggressive response.

Accidents can happen, of course, but wildlife photographers should strive to blend in with the scene and not be a source of interest and perhaps aggression.

14. Which photographer/s most inspired you and Mary Ann?

Way back, in 1968 or ’69, National Geographic ran an article about Frederick Kent Truslow, a bird photographer. As a teenager I was in awe of him, and in his article he explained his method for success.

Fred planned his images, envisioning what he hoped to photograph, and was patient, infinitely patient, to allow the behaviors to unfurl. I was inspired, and within a month I was carrying road-killed rabbits and groundhogs up a mountain to use as bait while I huddled in a rock pile, covered by a tarp, as I waited for turkey vultures to fly in.

It worked, and I got my envisioned shots, but I learned another lesson that day, too. I ran out of film after shooting a whopping two rolls, and I’ll never forget sitting in those rocks watching the vultures as they performed, kicking myself as I lamented my lack of film.

At any rate, Fred’s method was a revelation for me, and I realized that I’d just been a recorder before that, and not a shooter. Learning that lesson so early in my career was priceless.

And of course Fritz Polking, a name that should be familiar to any wildlife photographer who bothers to read photo credit by-lines, has always been an inspiration to me.

15. How do you encourage the next generation of wildlife photographers?

When I was a boy I wanted to be a herpetologist, and I wrote to the author of the reptile guide I had, asking his opinion on an observation I’d made with a snake. He wrote back, and I was honored, but I don’t think I really appreciated his response until I was much, much older.

In that spirit, we make it a point to reply to questions from beginning photographers, answering emails or letters. When our schedule permits it, we’ll help out with the student program run by NANPA during their annual conferences, and again, when we can, we've mentored an intern for the summer.

On a broader level, in this forum, we’d encourage the next generation of wildlife photographers by saying, first, that this pursuit shouldn't be about the money. It should be about the love, and as the saying goes, do what you love and the money will follow. Know your craft, and know natural history. If you don’t know your subject you’ll merely be a recorder, and your images will probably be shallow.

16. Any new courses or other things that you and Mary Ann are working on that you can tell us about?

Not much with courses, although this summer we’ll be offering our Flash Photography Course again, which we do only every few years. I’m hoping to get the new Photographing on Safari book finished, too.

We are scouting out new tour locations, including India for tigers, and Nepal and Bhutan for other subjects. We’re hoping to do more trips to Botswana, and pumas in Chile. As it stands, in 2011 we’ll be on the road for over thirty weeks, so finding the time for new courses and destinations will be a challenge.

About Joe McDonald...

Joe McDonald has been photographing wildlife and nature since 1966, starting with images of his pet turtles, lizards, and snakes he made as a high school freshmen. By high school he was selling photos to the National Wildlife Federation, and by his freshman year in college he was publishing in that magazine.

Since then, Joe's been published in every natural history publication in the U.S., including Audubon, Bird Watcher's Digest, Birder's World, Defenders, Living Bird, Natural History, National and International Wildlife, Ranger Rick, Smithsonian, Wildlife Conservation, and more. He is represented by multiple stock photo agencies, both domestically and world-wide.

He is the author of seven books:

• A Practical Guide to Photographing American Wildlife

• The Wildlife Photographer's Field Manual

• The Complete Guide to Wildlife Photography

• Designing Wildlife Photographs

• Photographing on Safari

• The New Complete Guide to Wildlife Photography

• African Wildlife, A Portrait of the Animal World.

His book, Designing Wildlife Photographs, was judged best book by the Outdoor Writers Association of America for 1994. In 1999 he produced Photographing on Safari, Joe and Mary's first instructional video. With Rick Holt and Mary Ann McDonald, he is also the author of Digital Nature Photography - From Capture to Output.

Joe is a founding member of NANPA, the North American Nature Photography Association, is a NANPA fellow and a former Board of Director for that organization. He has conducted multiple educational sessions at the annual NANPA summits, and he and Mary Ann have been Keynote speakers at this event.

He has also addressed nature photography groups around the country, in Arizona, California, Florida, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and elsewhere.

Joe and Mary Ann have placed at least thirteen times in the prestigious BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year competitions, more than any other husband/wife team. One year, Mary won two first places in this competition.

And then in 2013 Joe's image called “The spat” won in the category “Behavior: Mammals” in the BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition...!

To see more of Joe and Mary Anne's superb photos or to learn more about their photo safaris or books, please visit their Website.

All photographs on this page copyright Joe McDonald & Mary Ann McDonald

Return from Joe McDonald to Interviews Page

To make a safari rental booking in South Africa, Botswana or Namibia click here

"It's 764 pages of the most amazing information. It consists of, well, everything really. Photography info...area info...hidden roads..special places....what they have seen almost road by road. Where to stay just outside the Park...camp information. It takes quite a lot to impress me but I really feel that this book, which was 7 years in the making, is exceptional." - Janey Coetzee, South Africa

"Your time and money are valuable and the information in this Etosha eBook will help you save both."

-Don Stilton, Florida, USA

"As a photographer and someone who has visited and taken photographs in the Pilanesberg National Park, I can safely say that with the knowledge gained from this eBook, your experiences and photographs will be much more memorable."

-Alastair Stewart, BC, Canada

"This eBook will be extremely useful for a wide spectrum of photography enthusiasts, from beginners to even professional photographers."

- Tobie Oosthuizen, Pretoria, South Africa

Photo Safaris on a Private Vehicle - just You, the guide & the animals!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Please leave us a comment in the box below.