Interview with Guy Tal - Photographer, Writer, and Naturalist

1. Hi Guy. How did you get into photography and why a passion for landscapes?

I suppose you could call it a happy accident. I enjoyed hiking and exploring since I was a child. At one point I decided to try to document some of my excursions using my father’s old Minolta and, though my first attempts were not too successful, I discovered the joy of seeing more deliberately and identifying image-worthy subjects and compositions.

Early on I was more of a generalist and photographed pretty much anything. I remember spending hours chasing after birds and butterflies trying to capture them on film, not always with the best equipment. It was more of a trophy hunt than a creative pursuit and after a while I became bored with it and set the camera aside for a couple of years.

In my late teens and early twenties I also discovered American nature writing and became an avid reader of texts by Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and others. Among them was a book by Edward Abbey titled “Desert Solitaire” which fascinated me. In it, Abbey described the canyon country around Moab, Utah.

For years I wanted to visit and had no idea I would someday actually live in this area. I immigrated to the U.S. in my mid twenties and once I got established, I set off to explore some of the places I read about. In the process I discovered much much more. I also began to follow the works of American photographers and my interest in photography (and landscape in particular) was re-ignited.

2. When most people think 'landscape photography' they think ultra wide-angle lenses but you seem to favor 'normal' focal length lenses. What are your key landscape lenses?

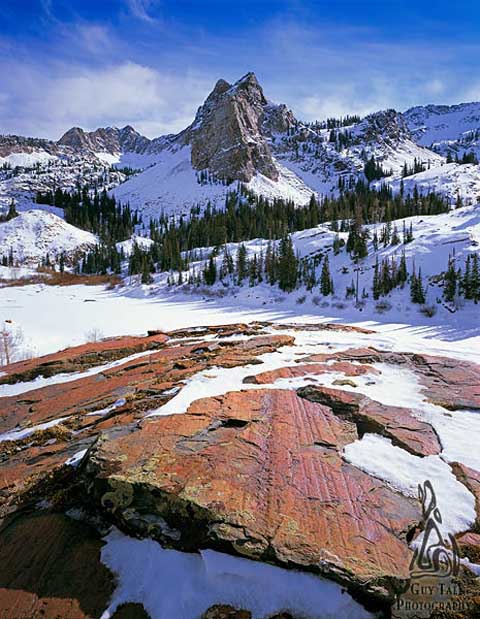

My style is perhaps best described as “Intimate Landscape”; a term coined by the great American photographer Eliot Porter. I think most people can intuitively understand what it means, though it is surprisingly difficult to define.

My goal today is to produce creative work, rather than merely document the places I visit. Intimate compositions are, to me, the manifestation of working a place creatively, looking for those things that intrigue me personally, composing them carefully and without visual distractions, illustrating what they mean to me personally, and coming up with original concepts.

In most cases these goals require isolating small vignettes out of the larger context of the area and normal/long lenses can be very useful for that.

Still, a couple of years ago I decided to put the theory to the test and loaded EXIF data from several thousand unique images into Excel to see how they are distributed by focal length. To my surprise, the graph was pretty flat. I use everything from ulta-wide lenses to long telephotos at about the same ratio so, yes, it is possible to make intimate composition even at very wide angles.

3. In addition to having the right equipment and knowing how to use it, the next criteria for a good wildlife photographer is knowledge of animal behavior. In order to be a good landscape photographer what are the 'other areas' of knowledge that are critical?

Primarily it would be a good understanding of the natural history of the area, weather patterns, seasonal variations etc. I don’t draw the line at understanding the physical properties of the place, though. In order for me to free my mind and work creatively, I need to be comfortable.

So, I like to know enough about the place that I can hike and camp there by myself, know about any potential dangers, pack and dress appropriately, know any laws or regulations that may apply, etc. Finally, I also like to be able to relate to a place on more than just a visual level so I always research the human history, stories, and anything else I can learn about it.

Ultimately, the more I know, the better my work will be, if only by putting me in the right state of mind, even if it is not directly related to what’s in the frame.

4. Please give us an idea of a typical day on one of your workshops.

Interestingly, I have not had a “typical” workshop yet. I like to tailor the content to the participants, and to specific conditions at the time of the workshops (season, timing, area, etc.), which means that each one is a little (or a lot) different from the others.

Generally I like to spend as much time talking about creative aspects of photography as I do actually practicing hands-on skills. We stop several times throughout the day to talk about creative concepts, review prints, discuss composition and technique etc. before heading back into the field to practice.

5. What are the three biggest mistakes your students tend to make?

I may not refer to them as mistakes necessarily since, in the end, it is about helping them accomplish what they want, not what I happen to believe is right. I find that the hardest thing for students to do is to let go of preconceptions and just listen to their inner voice.

This is evident by questions like “did I get the composition right?” or “where should I put my tripod?” I usually turn it back and ask them what they think they should do and just walk them through their own decision process. Second is the assumption that making an image ends when the shutter is released. I think we’re at a time where post processing has lost much of the appeal it had in the days of the wet darkroom (and even then many chose to avoid it).

Processing your images is one of the greatest opportunities for creative personal expression. Third is not being truly prepared for the challenges of working outdoors. To many, nature photography still means going to a national park, following the signs to a convenient viewpoint and capturing the same images that millions of others have before them.

I try to instill in my students a love for the wild and an ability to work in places where they are not in control and where an appreciation of the place is every bit as important as an appreciation for the photographs they hope to make.

6. In your 'Creative Landscape Photography' e-Book you discuss six distinct and progressive phases: Concept, Visualization, Composition, Capture, Processing, and Presentation. I would say that the concept and visualization stages are the critical ones - do you ever get photographer's 'block' and if so, how do you revive your creativity again?

I do, and I believe everyone does. It is a natural part of the cycle of creativity. The real challenge is to not let it bring you down. Recognizing the symptoms is the first step to recovery. If you know you’re in a slump, don’t push it.

Instead, use the time for other activities: read, look at other people’s work, go for a walk without a camera, take care of the less glamorous tasks like keywording or making submissions. I personally find writing during those periods very helpful in organizing my thoughts and coming up with new concepts, and others may want to pursue other creative outlets such as music or even cooking.

The most important thing is to recognize that these blocks are temporary and that you may as well use the time to charge your batteries and prepare yourself mentally and emotionally rather than stress yourself more.

7. In wildlife photography we are limited by the subject's movements but with landscapes your subject is stationary. How long does a typical landscape opportunity last for or how long do you typically spend with one subject?

It really spans the gamut. You’ll be amazed to know how many landscape images are ruined by movement or by rapidly changing light. Some scenes persist for hours and others require very quick reflexes to set up and capture the image while the light is right or during a lull in the wind.

8. With the advent of Photoshop and HDR software many photographers have discarded their filters. In your eBook your discuss ND and split-ND filters. Do these filters provide better results than software?

In general, they don’t, but in some situations they are more convenient to use and can save significant time in processing. If you capture the full dynamic range in the scene (whether in a single exposure or multiple ones) you have all the raw materials, but it may take quite a bit of work to combine them in a pleasing and natural way.

Personally I don’t mind spending time processing my work and enjoy the process so the only filter I use these days is a polarizer.

9. You don't mention a polarizing filter in your book - do you use this filter at all?

I do. It is the only filter that can’t be simulated digitally and I find it very useful in my work.

10. Have you experienced any 'e-book resistance'? This is where people have spent thousands of dollars on their photo equipment and are getting lousy photographs yet they simply refuse to spend a few dollars on an e-book!?

I received several emails from potential buyers asking why my eBook was more expensive than others on the market.

My standard response is that I’ll refund their money if they feel they did not get the value they paid for. eBooks come in all shapes and sizes and some go deeper than others.

Knowing how much time and thought went into it, I think it is priced fairly and sales were very good. So far I was not asked for any refunds.

11. With so many photographers shooting the same subjects, using similar equipment and taking classes from the same people, how can landscape photographers differentiate themselves? Is it enough to just look for the intimate landscapes instead of the more common wide vistas of favorite places?

I don’t think so. There are many ways to differentiate. One is to simply be a good marketer. Even mediocre work can sell very successfully and gain a lot of exposure in the hands of a marketing expert. Unfortunately, I am not one.

My own belief is that great photography is distinct in two aspects: creativity and skill. Creativity yields original, personal work, which is unique to the photographer and is readily associated with them rather than becoming yet another anonymous take on a familiar place. Skill is needed to properly capture, process, and present the work.

Even great images may not make the cut if they are poorly presented. My advice to aspiring photographers is to think not only about the things that make a great image but also of the things that make it your image. Just because it is captured by your camera doesn’t make it your image. It also needs to tell your story, which is different from everybody else’s.

12. You have a post on your photo journal entitled 'Teach Yourself Photography in 80 Years' where you mention finding a few online photography eBooks that proclaim to teach the buyers photography skills in anywhere from 24 hours to 14 days. Is it possible to learn the art of photography so quickly or is this a classic case of false advertising?

In such a short period of time, the best you can hope for is to understand how photographic equipment works and to gain some practice in operating your camera. You may also learn about basic concepts of composition and some processing techniques.

This will not make you a photographer, though. It is only the first step in a journey that may well last the rest of your life. I like to compare it with writing: learning how to operate a word processor and a basic understanding of grammar and punctuation will get you started, but it will not make you a novelist.

13. Guy, what are your top-tips for someone wanting to improve their landscape photography?

My #1 tip to anyone asking this question is to simply spend more time in the field. The more time you have with your subjects, the more inspired you will be, the better your chances are of seeing something unique and being there at the right time, and the more opportunity you have to experiment and learn.

Second is to resist the urge to tie your successes or failures to gear. If I had to choose between a $30,000 camera and a $30,000 travel budget, even if it meant going with just basic camera equipment, I’ll take the latter without hesitation!

If you have a decent camera and a couple of lenses, set aside your gear lust (difficult, I know) and become a student of light, of composition, of master artists in any discipline and, more than anything: pursue and develop your inspiration.

Think of the things that got you interested in photography in the first place and find ways to experience them on a more frequent basis and to the greatest depth possible.

14. Any new Guy Tal books or workshops coming up?

I am now working on my second eBook in what I call the “Creative Series”. The next title will be dedicated to Creative Processing Techniques.

I am temporarily not offering workshops at this time due to other priorities but hope to resume them in the near future.

About Guy Tal

Guy Tal is a photographer, writer, and naturalist living and working in the Colorado Plateau - a scenic and diverse desert region of the western United States spanning an area larger than most countries and states.

Over the years, this magical and endangered landscape had not only been his home but also his sanctuary and his main source of inspiration.

It is Guy's goal as a person, as a writer, and as an artist, to promote and to share its wild beauty, and advocate for its preservation. It is a place like no other - a treasure for the soul that future generations deserve to experience in its wild state as we have been privileged to.

Guy is often asked about the visual qualities of his work and how they relate to the elusive concept of "reality". He strongly believes that photography is the most restrictive of the visual arts but at the same time also has the potential to make the most impact with the viewer for one simple reason: photographs have a binding connection with real events, real elements, real light, and real moments in time.

Any obvious departure from these realities will cause an image to be dismissed outright regardless of any other aesthetic qualities it may possess. The photographic artist's tools are primarily well-crafted composition and careful adjustments of the captured image within very narrow margins.

His goal is to produce images that inspire without venturing outside the realm of the believable. The ability to imbue a photographic image with one's personal thoughts and emotions is indeed what puts the "art" in Fine Art Photography.

To be clear, Guy's images may well represent a personal interpretation that may differ from, extend, or even alter what others may regard as a strict documentary rendition of a scene. They are to be regarded as works of creative art, though they are always based on real elements and express a real reverence for the subjects portrayed.

To see more of Guy's images or to buy his eBook please visit his website and his Guy Tal blog.

All images on this page are copyrighted © Guy Tal. All Rights Reserved.

Return from Guy Tal to Interviews page

To make a safari rental booking in South Africa, Botswana or Namibia click here

"It's 764 pages of the most amazing information. It consists of, well, everything really. Photography info...area info...hidden roads..special places....what they have seen almost road by road. Where to stay just outside the Park...camp information. It takes quite a lot to impress me but I really feel that this book, which was 7 years in the making, is exceptional." - Janey Coetzee, South Africa

"Your time and money are valuable and the information in this Etosha eBook will help you save both."

-Don Stilton, Florida, USA

"As a photographer and someone who has visited and taken photographs in the Pilanesberg National Park, I can safely say that with the knowledge gained from this eBook, your experiences and photographs will be much more memorable."

-Alastair Stewart, BC, Canada

"This eBook will be extremely useful for a wide spectrum of photography enthusiasts, from beginners to even professional photographers."

- Tobie Oosthuizen, Pretoria, South Africa

Photo Safaris on a Private Vehicle - just You, the guide & the animals!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Please leave us a comment in the box below.